The Foundational Economy is an evolving approach to socio-economic development which focusses on the provision of everyday universal basics like food, housing, health services and transport within planetary limits. It offers a distinctive socio-economic analysis of the mess we are in and a politics of improvement from where we are at. The political approach varies in what to do and how to do it according to analysis of time and place, and foundational analysis has developed over time through internal debate and response to external criticism.

Over the decade since 2013, researchers and practitioners in several European countries have contributed to this development and at any moment in time there are differences and debates within and between national groups. The account below represents the current understanding of the British group of researchers who have authored the key English language publications, together run an action research agency Foundational Economy Research Ltd and join with practitioners in Foundational Alliance Wales, which networks change makers1.

The most basic point about foundational economy is that it is not always the same. It is a developing body of thinking and doing where, as this introduction explains, old elements are carried over and embedded in analysis of the changing conjuncture. Foundational economy has evolved over a decade (2013-23), and we would identify three milestone English language publications which each represent a major step on the foundational journey.

- In 2013, the Foundational Economy Manifesto2 introduces a zonal understanding of co-existing economies, borrowed from the French historian Fernand Braudel. It argues against the idea of a unitary economy where all activity is or should be subject to one logic and set of principles, Instead, “the economy” is divided into zones, each one with different principles, ways of working and objectives. Politicians obsess with the tradeable sector and focus “industrial policy” on this relatively small sector, aiming to improve competitivity especially in glamorous, high tech new industries. But, for ordinary citizens, what matters more is the foundational economy. This is the large, neglected and sheltered zone of the economy which employs around 40% of the workforce and provides households with basic goods and services like healthcare, education, utilities and food.

- In 2018, the Foundational Economy book3 broadens the discussion from rethinking the economy to doing politics and policy differently. In terms of politics, it argues that entitlement to foundational provision is the substantive basis for the actual exercise of citizenship which, must otherwise remain an empty, formal status4. Neglecting the Foundational Economy is hence not simply an economic choice but an erosion of

- democratic rights. In terms of policy the 2018 book began to discuss what could be done to reinvigorate the Foundational Economy and identified a set of preconditions. They included asking citizens about their foundational priorities, instituting social licensing to ensure corporate business delivered on social priorities and encouraging small and medium-sized private and social enterprises and refinancing the state by reinventing taxation. A second edition in 2022 included a new preface which usefully summarises developments in the years since first publication5.

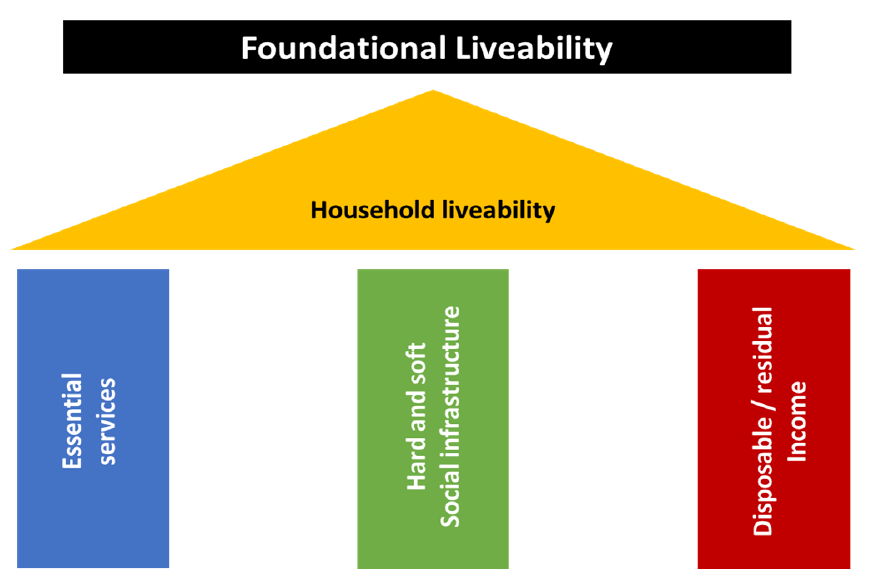

- The 2023 book When Nothing Works6 presents arguments and evidence that take us several steps further without undermining the original arguments about the importance of the foundational zone and the emphasis on citizenship. The book consolidates several years of work by the British team of researchers not just into activities but also into places. This body of work includes a pioneering study of the South Welsh district town of Morriston7 which highlighted the importance of social infrastructure and a ground-breaking study of deprived wards in Newcastle upon Tyne which highlighted residual household income and travel to work issues8. On the basis of this learning, the 2023 book made several further steps. It introduced the three-pillar concept of liveability dependent on the alignment of the pillars of residual income, social infrastructure and essential services. It insisted the unit of analysis for liveability should be the household, not the individual. And, finally, it proposes an “adaptive reuse” approach to policy in the 2020s, which works around the constraints that frustrate mainstream policies.

If you have to choose one English language source, the 2023 book offers an up-to-date statement of position and is available as a cheap paperback. Before or instead of reading the 2023 book, this introduction explains where we are coming from and details the development of foundational thinking and doing.

In other languages, there are a variety of book length introductions.

- The 2018 Foundational Economy is a general introduction and has been translated into German as Die Okonomie des Alltaglebens9 (2018); into Italian as Economia Fondamentale10 (2018); into Portuguese as Economia Fundamental11 (2021); and Turkish as Yaşamin Temel Ekonomisi12 (2022). The Portuguese and Turkish editions add new prefaces for those audiences, with the Turkish preface arguing the relevance of foundational economy to low- and medium-income countries.

- National specifics matter and therefore local groups have produced national analyses, Belgian and Dutch readers are served by De Essentiele Economi13 (2022). And the Italian group has produced its own manifesto in Il Capitale Quotidiano14 and an overview Prima I Fondamentali 15(2022).

1. Radical Orientation

Those who are concerned to pigeonhole new ideas often ask where foundational economy stands on the left/right continuum which they understand as a preference for state or market. This framing of the choice is not sensible when financialised capitalism brings us not the market but monopoly with platform capitalism and outsourcing conglomerates feeding off the state. And in our case it is irrelevant because we are neither left nor right but radical liberal collectivist with an understanding of the limits of market mechanisms and state intervention.

Foundational thinking is liberal because of its aims. As Amartya Sen argued16, development should enable citizens to live the lives they have reason to value (not to meet a set of needs we define for them or to expand market output and improve competitiveness). On this basis, the role of public policy is to facilitate the demand and supply side preconditions for living such lives of freedom. From this point of view, policy should not directly aim to increase well-being or to secure happiness because, in foundational thinking, wellbeing is an outcome of the responsible exercise of freedom, and human happiness is the often-transient consequence of individual and collective choices.

Foundational thinking is collectivist because everyday basics like health services will not be accessible for all according to need if they are made matters of private consumption from individual income. The implication is that public policy should balance any concern with growth of incomes with a clear focus on renewing collective provision of essential services and social infrastructure. In the current nature and climate emergency, renewal is an urgent priority because basics like transport and housing are major sources of emissions. This broader view separates foundational thinking from national income accounting which adds up the financial value of output and incomes as though market value represents the superordinate order of worth.

At the same time foundational thinking is agnostic about forms of ownership. There is no one best way because the appropriate form of ownership will vary according to the activity, the business model and the capability of the operator. Thus, the expansion of state and social enterprises into risk investment domains is ill-advised because such enterprises do not have the governance nor management capacity for successful investment where revenues and profits are uncertain17. Equally, utility privatisation and service outsourcing were definitely a mistake insofar as they admitted extractive operators to feed off guaranteed revenues; and, at the same time, they eroded state capacity to organise and control complex operation so that it is difficult to reverse the mistake.

Strong collective foundations and appropriate ownership are becoming more important in an increasingly unstable world. The notion of poly crisis caused by interacting multiple crises understates the extent of these problems18. In foundational thinking, the problem is that by the 2020s we all live in an earthquake zone at the intersection of a series of fault lines about (1) an unstable debt based financial system (2) long, vulnerable commodity supply chains (3) great power competition in a multipolar world (4) pandemic threat to public health against a background of (5) nature and climate emergency. We cannot predict the next quake and know only that ineffectual response to the last quake has exhausted national governments and increased the mess we have to live with.

Foundational economy can thus be understood as a radical reinvention for disorderly times of the Beveridge and Keynes tradition of liberal collectivism whose collapse in the 1980s was documented by the older members of the British team19.

2. More a construction site than a closed system

The foundational economy’s distinctive socio-economic analysis and politics of improvement for the 2020s have developed partly out of dissatisfaction with the academic mode of knowledge production, in increasingly narrow specialised disciplines which generate debates for small communities who read the same literature. Unlike academic social science, Foundational Economy brings together researchers and practitioners in action research so that conceptualisation, intellectual system building and critique is combined with facilitation and implementation of positive social innovation.

As outward looking researchers and practitioners, we are concerned to understand the specificity of activities and the implications of a changing conjuncture for the possibility of improvement and the necessity of change. Hence, the British team of researchers has produced a range of reports on a diverse range of Welsh activities from afforestation to small towns to health services, where progressive enterprises and alliances were already at work, but system change is elusive20. Quake events like the Covid pandemic, “the cost-of-living crisis” and the ensuing government response are a learning opportunity for developing foundational thinking and doing (rather than fitting events into a pre-existing framework).

If Foundational Economy is a work in progress, it is in unsteady evolution, stimulated by events, policy changes and enterprise innovations as foundational researchers and practitioners respond to new and old activity challenges in different places and at different levels. Thus, the aim is not for paradigm change by producing an intellectual system which is closed, in that it fixes relations between variables in a defined field of the visible. The ongoing result is more like a construction site where the building grows without a constraining master plan as researchers and practitioners work by adding extensions.

The direction and design of the extensions depends on how established foundational researchers and practitioners respond to activity specifics and events in a changing conjuncture, and on how newly recruited researchers and practitioners join the collective and introduce new concepts, perspectives and issues.

Some of the practitioner developments will be noted in this introduction’s fourth section on social innovation through adaptive reuse. Here we can note some of the more important research developments since the original 2013 Foundational Economy manifesto.

- The insistence by Austrian researchers that the FE is a cornerstone of social-ecological transition on a damaged planet21. Correspondingly, British researchers argue we now need FE 2.0 which recognises the environmental problems now being created by FE 1.0 systems of the 1870s-1950s which made urban living safe and civilised22.

- An important stream of work relating systems to place. This was led by the conceptual work of Schafran et al. on urban reliance systems and the importance of a spatial contract which guarantees the availability of basic services in towns and cities23. This has been followed up by place studies of politics and planning in a Vienna suburb24 and Welsh small towns25.

- The collective’s response to Covid 19 took the form of a manifesto translated into four languages26. The British team backed this with an extended report which blamed the ineffectual pandemic response of the English NHS on underfunding that had created a fragile, high flow hospital system and an over centralised public health laboratory system27.

- The work of construction gathers pace when the next book in the Manchester Capitalism series is Justin O’Connor’s Culture is Not an Industry which claims culture as foundational 28 and this will be followed by Kevin Morgan’s Public Plate book on food in school, hospitals and prisons.

All this is a matter of extension which develops and builds on earlier positions. So, for members of the collective, doing foundational economy is going on a journey. As we have noted, at any one time there will be differences of opinion and internal debate about recent and forthcoming developments. But equally at any one time, there is a unifying focus for research and practice reform. As argued in the next section, the current focus is on household liveability.

3. The current research focus on household liveability

Liveability – the capacity to thrive by enjoying freedom – is our current focus, and the thread which connects several different streams of research and innovations in practice. The starting point of these various streams is the idea that, if economy and society exist to enable Senian freedom, then the practical goal is to sustain and improve liveability by tackling the various preconditions of liveability at household level.

This emphasis on the household breaks with the social science of the past 50 years which has taken the individual (and often the average individual as in GDP or GVA per capita) as the unit of analysis when conceptualising welfare, prosperity and wellbeing. Against this we observe that 70% of UK citizens live in multi-person households sharing expenditure; and income sharing has become more important with the rise of female workforce participation so that both parents work in 75% of UK households with children. The household has become the unit which increasingly consolidates two sources of income as well as pooling expenditure so that, for example, single parent households are on average seriously disadvantaged in financial terms29.

This observation of what exists in diverse household forms has nothing to do with the radical right’s conservative values and nostalgia for the traditional family combining a male head and a childbearing woman. But the implications of taking households as the unit of analysis are radical. Because policy in all high-income countries has privileged making the economy work to generate growth from increased productivity, which could sustain higher wages and tax revenues to pay for public services. The foundational alternative is making the household work by directly tackling the preconditions of foundational liveability.

The temple of liveability diagram in the When Nothing Works book then summarises the foundational framing of the conditions of household liveability30. The household income that matters is not gross wages but (1) residual income after paying for the FE4 universal basics of housing, utilities, food and transport. Just as important as residual income is (2) household access to universal services like health and education and (3) the social infrastructure which is necessary because we are social animals.

From the three pilar point of view, the current “cost of living crisis” is part of a larger, longer-term crisis of liveability caused by the crumbling of all three pillars of liveability. Public services and social infrastructure crumbled in the UK through underfunding in the austerity decade of the 2010s. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, governments persisted with unreformed income and consumption-based taxes while cheap money boosted asset values and wealth inequalities. Then, after the start of the Ukraine War, the energy price spike and food price inflation dramatically reduced the residual income of low paid households which then often had to choose between heating and eating.

In the current conjuncture, the pursuit of household liveability on the demand side is bounded by supply side conditions. Here responsible and capable firms are important because such firms are – or can be – both providers of decent jobs for wage earners and suppliers of quality goods and services to households. Financialization (with its emphasis on private capital returns and austerity public budgeting) has effectively eroded the motivation of private firms and the capacity of public organisations to supply households with these basics. Hence supply-side reform is the corollary of improved household liveability. But foundational “industrial policy” is not focused on high tech innovation sectors and productivity gains which never materialise; instead, the aim is social innovation in goods and services provision and decent working conditions as much as fair wages.

Against a background of nature and climate emergency, liveability in today’s ecological crisis must be rethought by recognising the pressing need to restore and enhance natural ecosystems – which are the ultimate foundations of life on this planet. The solutions of one generation have become the problems of the next. Existing foundational provision is a big part of our current problems because more than half our emissions now come from foundational provision, especially food, transport and energy. As the position paper on Foundational Economy 2.0 argues31, this poses new challenges which are about decarbonizing existing foundational reliance systems like the mobility system, as well as challenges about building new reliance systems like what we have called ‘the wood economy” which would replace steel and cement with home grown timber.

4. “Adaptive Reuse” and social innovation through engine organisations

In our complex polities, under multi- level government, not for profits and private interests all have agency within multiple governance systems amidst contesting orders of worth. How should we go about changing things in this messy context? Mainstream foundational economy rejects modernist reform through grand redesigns which promise transition and transformation32 but deliver unexpected problems at high cost. Instead, foundational economy favours reform by bricolage from where we are, by reusing what is to hand. This is the approach which the French architects Lacaton and Vassal term “adaptive reuse” with the slogan “never demolish, always add, transform and reuse”33.

The actors with agency to drive adaptive reuse will vary according to time and place. After a decade of austerity and in the crisis ridden 2020s, governments are distracted by multiple objectives (including anachronisms like economic growth) and increasingly lack the resources and management capability to initiate large scale change. Government cannot be ignored because it is a source of legitimacy and funds at the upper levels and a potential supporter at the lower levels. But constructive government is now less about doing things and more about convening and facilitating change when government will in many cases follow rather than lead social innovation.

In the current conjuncture, the initiative for change will often come bottom up from civil society and all the institutions between the state and the household. At a micro level, community led development is important for reusing the assets within community reach to address social and ecological challenges. Hence, the community pubs and the local food networks. But at meso level, we have to rely on a diverse range of intermediary organisations to deliver change at a scale which can make a regional difference. In the UK at present, these intermediaries include housing associations, health trusts and boards, care providers and for-profit locally grounded SMEs (small and medium enterprises). All of these are valuable insofar as they have management capability and can mobilise financial resource for social innovation.

The foundational objective is more and better intermediary enterprises of all kinds delivering community benefits for improved household liveability. The aim is to turn “anchors” doing a few things like invoice-based local purchasing into engines of radical social innovation. An engine is a community benefiting enterprise, using its agency for social innovation either by delivering goods and services differently and/ or by extending the range of goods and services offered.

The good news is that many community benefitting organisations have started doing foundational liveability actions because they have the right values. They have innovated, often without having read our research, and with little or no publicity for their achievement. Welsh examples include:

(1) Changing adult care from time and task to a patch system, as in Gwynedd Home Care, with increased responsibility for the worker and teamwork between a trusted care supplier and other agencies.

(2) Extending the social housing service offer (while not neglecting basics), as with the Clwyd Alyn Housing Well Fed programme, at the same time as managing tenancies for no evictions in four years34.

(3) In labour intensive health care, Aneurin Bevan and Hywel Dda Health Boards have developed “grow your own” workforce development35. This allows care assistants with few academic qualifications to become registered nurses, so that professional entry is opened up.

(4) Merthyr Valley Homes has introduced a “4-day week” or shorter hours for its workforce delivering the same quality of service. This gift of time is especially important for low paid workers who cannot afford to outsource services and who are managing caring responsibilities.

(5) In urban renewal we have innovative business models for in-town brown field redevelopment as with Coastal Housing building up on Swansea High St or Galeri Caernarfon linking a series of developments across their town.

These examples show that the future is already with us, but it is unevenly distributed as the social innovations listed above remain local and their good practice does not travel. The adaptive challenge is to consolidate, upscale and institutionalise bottom-up prefigurative experiments and hence make the change structural. In tackling this challenge, a Welsh group of foundational researchers and practitioners has emphasised the importance of mobilising political alliances on the basis of shared understanding and an evidence-based approach to tackling place and sector specifics Given the chain interconnectedness of many activities in areas or sectors, agency and leverage often depend on alliances for change that span government, third sector and for profit organisations, including enterprises of different size.

Luca Calafati, Julie Froud, Colin Haslam, Sukhdev Johal and Karel Williams, August 2023

- For which see the websites at https://foundationaleconomyresearch.com/ and foundationalalliance.wales ↩︎

- J. Bentham et al (2013) “Manifesto for the Foundational Economy” (CRESC Working Paper 131) https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/wp131.pdf ↩︎

- J. Froud et al (2018) Foundational Economy, https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526133984/ ↩︎

- Foundational arguments about citizenship have subsequently been developed in F. Barbera and I.R. Jones (eds. 2020) The Foundational Economy and Citizenship https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/the-foundational-economy-and-citizenship ↩︎

- J.Froud et al. (2022 second edition) Foundational Economy, https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526164681/ ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al (2023) When Nothing Works https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526173713/ ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al. (2019) “How an ordinary place works” https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/morriston-report-v6-13-may-2019.pdf ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al. (2022) “Jobs and Liveability” https://foundationaleconomyresearch.com/index.php/recent-research-reports/ ↩︎

- https://www.suhrkamp.de/buch/foundational-economy-collective-die-oekonomie-des-alltagslebens-t-9783518127322 ↩︎

- https://www.einaudi.it/catalogo-libri/problemi-contemporanei/economia-fondamentale-collettivo-per-leconomia-fondamentale-9788806241605/ ↩︎

- https://www.almedina.net/economia-fundamental-as-infraestruturas-do-quotidiano-1604568034.html ↩︎

- https://www.imge.com.tr/kitap/yasamin-temel-ekonomisi-gunluk-yasamin-altyapisi-julie-froud-9789755339702 ↩︎

- https://www.aspeditions.be/en/book/de-essentiele-economie/18275 ↩︎

- https://www.donzelli.it/libro/9788868434861 ↩︎

- https://fondazionefeltrinelli.it/schede/prima-i-fondamentali/ ↩︎

- A. Sen (1999) Development as Freedom. It should be noted that the Austrian team dissent and ground their version of foundational economy in human needs. ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al (2023) Municipal Trading Then and Now, https://foundationaleconomyresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Municipal-Trading-then-and-now.pdf ↩︎

- K. Whiting (2023) “This is why poly crisis is a useful way of looking at the world right now” https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/polycrisis-adam-tooze-historian-explains/ ↩︎

- T. Cutler et al (1986) Keynes, Beveridge and Beyond. ↩︎

- For the range of recent Foundational Economy Research Limited reports by the British team, see the relevant section of their website: https://foundationaleconomyresearch.com/index.php/recent-research-reports/ ↩︎

- R. Bärnthaler et al. (2021) “The Foundational economy as a condition for social ecological transformation” Sustainability, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/18/10460 ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al. (2021) “Meeting social needs on a damaged planet”, Working Paper no 8. https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/fe-wp8-meeting-social-needs-on-a-damaged-planet.pdf ↩︎

- A. Schafran et al. (2020) The Spatial Contract https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526143372/ ↩︎

- R. Bärnthaler et al. (2022) “Social-ecological politics for everyday life” https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/baernthaler-fec-report-final-5-may-2022.pdf ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al. (2021) “Small towns, big issues” https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/small-towns-big-issues-report-june-2021.pdf ↩︎

- Foundational Economy Collective (2020) “What comes after the pandemic“

https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/what-comes-after-the-pandemic-fe-manifesto-005.pdf ↩︎ - J. Froud et al. (2020) “When systems fail “ / https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/when-systems-fail-uk-acute-hospitals-and-public-health-after-covid-19.pdf ↩︎

- J. O’ Connor (2023 forthcoming) Culture is Not an Industry, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Culture-Not-Industry-Reclaiming-Manchester/dp/1526171260 ↩︎

- L Calafati et al. (2023) When Nothing Works, pp. 71-81 ↩︎

- L Calafati et al. (2023) When Nothing Works, pp. 81-94 ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al. (2021) “Meeting social needs on a damaged planet”, Working Paper no 8. https://foundationaleconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/fe-wp8-meeting-social-needs-on-a-damaged-planet.pdf ↩︎

- It should again be noted that Austrian foundational researchers do use the terms transition and transformation. ↩︎

- J. Froud et al. (2022) Foundational Economy (2nd edition) “Preface to 2022 edition”. ↩︎

- https://www.cancook.co.uk/about-well-fed/ ↩︎

- L. Calafati et al. “NHS Wales as a driver of economic value“ https://foundationaleconomyresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NHS-Wales-Public-Interest-Report-June-2022.pdf ↩︎